Infopool @ Tate Modern

9.2.2001

On 6th February,

a week after the Century City show opened at the Tate Modern, we learnt

that the three Infopool pamphlets first circulated in summer 2000 had

been used as part of the London contribution in the Turbine Hall. The

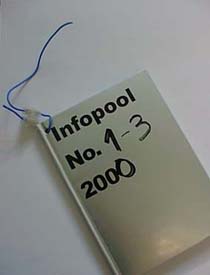

format of the pamphlets had been altered: the three seperately published

pamphlets had been renumbered, compiled and bound as a hardcover book

to give them a uniformity with other documents on display: artist's monographs

published by Phaidon, artists' books and magazines etc. We were not contacted

about the use or alteration of these pamphlets by any representative of

the Tate gallery even though each one carries an e-mail address. When

looking more carefully into this, to clarify how the pamphlets were used,

i.e. whether they were included as a contribution to an adjacent reading

room or whether they were used as 'documentary' exhibit in the main body

of the London display, we found that the pamphlets had been used more

as an exhibit than as supportive material.

|

As ongoing samples of various practices united under the Infopool project their appearance within the Century City show reconfigures them as discourse objects. On display in a new hardback cover and threaded through with wire (the new vitrine) the pamphlets take on an aura that undermines both their form and content. They are no longer able to be passed on, given as gifts, and circulated to friends and fellow travellers i.e. to be self-institutional. In short the pamphlets have been commodified beyond their informal and nominal £1.00 price. The generator of value that is the Tate Modern has allotted them an immaterial cultural value (prestige, distinction) in exchange for the appearance of the value of their autonomy. Remember we were not party to such an exchange. Acting autonomously and in terms of a new relationship based on trust rather than ownership and with respect to our future collaborators we hereby claim the right to re-appropriate the pamphlets.

We have no doubt that this not only refers to a gross misunderstanding on the part of Tate curators but also to the improvised way in which Infopool operates. We are defining our practice as we go along - projects that appeal to our desires, that can give reign to the desire to know, experiment and communicate, are chosen rather than our sitting down and defining Infopool in the manner of a manifesto or a movement. That the pamphlets have turned up at Tate Modern may be cause for reassessment (how do we defy the commodification of knowledge? how do we attempt to profile a new social relation?), but why should Infopool, which has been 'established' to enable the creation of a fledgling conceptual space, to link-in with other secessionist efforts to redefine the 'public domain', have to be forced to be defensively ideological every time it produces a small run pamphlet? We perhaps idealistically assumed that all those who showed an interest in the pamphlets would thereby respect their ethos: that we were offering to them the escaping values of desire - exodus towards self-institution.

The gross curatorial misunderstanding is related to a gross overestimation of the power museums like Tate Modern have in culture. Sadly many believe in this power and would be only too happy to have their projects included in such shows as Century City. We wonder whether it is this very illusion of power and the fact that those wielding it feel certain that everyone else wants a share in it that led to a whole team of Tate curators to neglect to approach us for our consent to this new exchange of values, this re-commodification of the pamphlets that is the real basis, however unconscious, of the Tate's power? Is it also that this overriding view of cultural practices as commodities and the curators' role as re-commodifiers that gives them the feeling of ownership over the pamphlets? Within the Infopool network culture is understood as a social relation. The Tate Modern trades on that social relation as 'art', it packages it as an event, a revolving spectacle that recontextualises contexts and activates a form of value that was never intended. Infopool is the effort of a social relation which attempts to resist commodification. We feel that the vulnerability of the Infopool project - it's unprotected offer of communication, its fledgling self-institution - has been exploited in an episode that reveals to us not only the reconfigured colonialism of a desperate institution, but the ongoing valorisation of socialisation that more institutions than Tate Modern are engaged in. Again we reaffirm the right to re-appropriate them. We picked the pamphlets up on Friday February 9th. To negotiate their exit would have taken too long.